The child care industry is pivotal for parents being able to work and for children’s early learning. It struggles to compete for workers.

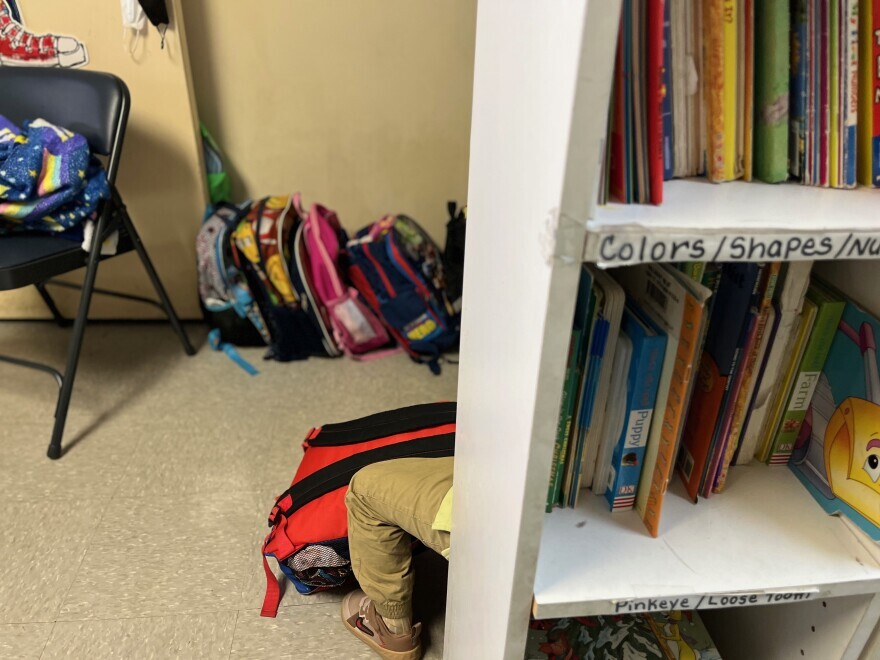

Traffic was roaring up and down NW 27th Avenue in Miami, but most of the children inside 1 World Learning Center snoozed away one afternoon last week.

It was nap time at the preschool.

The soft sounds of three and 4-year-olds sleeping on green cots with their blankets wrapped around them filled their classroom. There was soft music playing for the younger children in other rooms. Two infants hadn’t yet settled down. One four-month-old was rubbing her eyes and crying softly.

That Monday, 23 children were at the school ranging in age from four months to four years. That was about half the number the center usually cares for, according to owner and director Antoinette Patterson.

You turn to WLRN for reporting you can trust and stories that move our South Florida community forward. Your support makes it possible. Please donate now. Thank you.

She’s run her daycare at this location since 2015. She started in the child care business almost 20 years ago. She’s been through economic recessions, hurricanes and now a global pandemic.

She called the early months of the pandemic “chaos” amid a mad rush for masks, gloves and cleaning supplies. That has given way to awareness, vaccines for most people (except young kids), and treatments.

“We figured it out,” said Patterson.

In March 2020 child care centers were encouraged to stay open. Their staff were among those deemed essential workers in Florida. Schools, restaurants and bars were ordered closed, but not child care facilities.

“You still had police workers and nurses who had to work, the doctors have to work, the correctional officers. We still have parents that had those careers,” she said.

Tens of millions of dollars were included in the first federal COVID emergency spending package for child care in Florida. Patterson’s preschool secured several emergency loans and grants, including a $133,000 Emergency Injury Disaster Loan from the Small Business Administration. It also received two Paycheck Protection Program loans, each about $17,000. Both have been forgiven. The business secured a separate $6,000 grant from the Small Business Administration, too.

The preschool is in a zip code where just over half of the households make less than $50,000 a year according to Census Bureau data. That’s a few thousand dollars less than the average household income in the county. The area is about 70% Black.

Antoinette Patterson started 1 World Learning Center in 2005 in Opa Locka. It has been on NW 27th Ave in Miami-Dade County since 2015.

The younger the child, the more expensive the care is, starting around $250 per week for babies. Most of the parents sending their children to 1 World Learning Center qualify for a subsidized fee, according to Patterson.

Attendance is less than before the pandemic, but the subsidized fee was increased early in the pandemic. That has helped Patterson raise the hourly pay rate for her teachers. Starting pay is between $12 – $13 an hour. She offered a $600 hiring bonus, but didn’t get any bites.

“We can’t afford to compete with Burger King or McDonald’s paying maybe $13 an hour. We find ourselves in a rut. It’s hard for us.”

Antoinette Patterson, Owner/Director, 1 World Learning Center

Wages and employment in the child care industry have been rising in South Florida. Median pay was up 20% last year from a year earlier. Still, it remained below $14 an hour. And while the number of people working in daycare nationwide dropped by more than 20% between May 2019 and May 2020, it grew by 5% in Florida.

“You see help wanted signs everywhere because it’s extremely difficult to find people to work,” said Florida Policy Institute Senior Policy Analyst Norín Dollard.

“Child care has historically not been a very high paying job. It’s a very rewarding job. And we’re really grateful to the people who do it. But it’s not a lucrative occupation by any means. People (aren’t) seeking jobs in the same way that they were before the pandemic,” Dollard added.

And there are fewer people in the traditional labor pools from which the child care industry would usually hire.

While the overall job market has bounced back from the pandemic depression, there are still fewer jobs today and few people available to work in South Florida than before the pandemic.

The labor force in March was 1% smaller than the month before COVID-19 led to restrictions. That may not seem like a lot, but in South Florida, that’s more than 50,000 fewer people in the job market.

Statewide, men are back at work in the same numbers as before the pandemic, but not women.

“The child care burden, even at this juncture, tends to fall predominantly on women. So where child care is not available or affordable, women — if they left the workforce — they’re not returning in quite the same numbers that men are because of their caregiving responsibilities,” Dollard said.

That’s especially true for Black women in Florida. The latest data from 2021 shows the number of Black women in the job market and the number of Black women working in the state were still down 2% from pre-pandemic levels even with the broader job recovery.

This article originally appeared: https://digital.modernluxury.com/publication/?m=46825&i=730294&p=182&ver=html5